Frost remains one of the most unpredictable and damaging risks for grain growers in the WA Wheatbelt. Even with careful management, it slices into profits year after year.

Sowing Strategies in the Facey Catchment

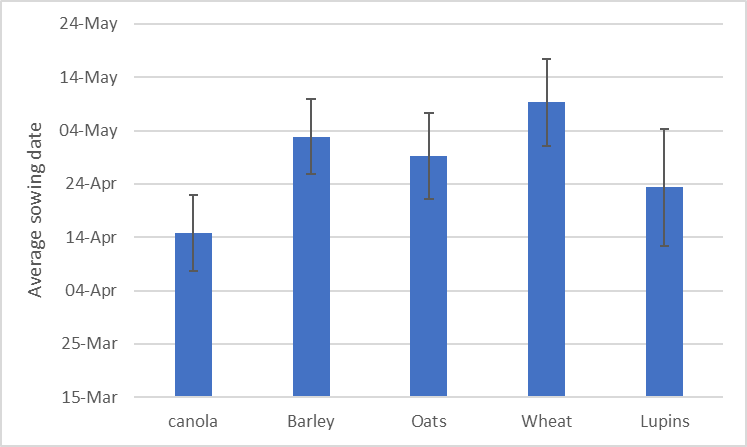

Sowing time is one of the key tools farmers use to manage frost risk. Within the Facey Group:

- Canola is typically sown first in mid-April to maximise the growing season.

- Lupins, oats, and barley follow.

- Wheat is sown last, around early May, because it is most vulnerable to frost damage at flowering.

This sequencing helps spread risk and protect wheat yields, while still making use of the earlier break for other crops.

(Figure 1: Average sowing dates for major crops in the Facey catchment)

The Economics of Frost

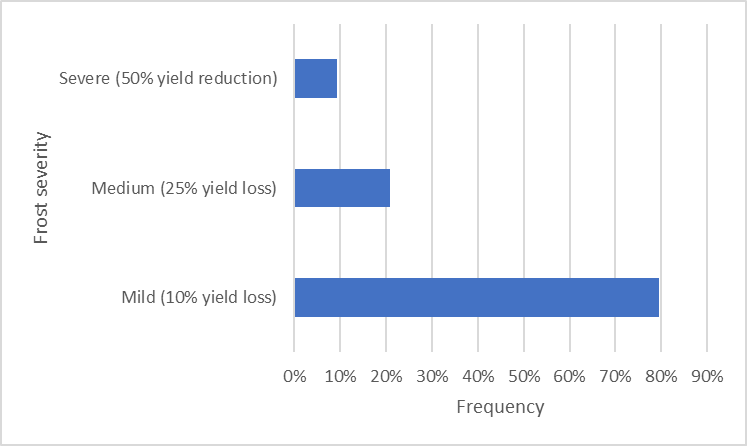

Growers across the Facey Group report that frost is not a rare event — it’s a recurring cost of farming:

- Severe frost (50% yield loss): ~1 in 10 years

- Medium frost (25% yield loss): ~1 in 5 years

- Mild frost (10% yield loss): the majority of years

(Figure 2: Frequency and severity of frost events)

On average, this adds up to a long-term yield reduction of ~370 kg/ha in wheat. At current grain values, that’s about $130/ha, or $103,600 per farm (based on an average 800 ha wheat program in the Facey catchment).

How Growers Manage Frost

To limit losses, Facey Group growers already employ a range of strategies:

- Plant less wheat and diversify with other crops.

- Spread flowering time with multiple cultivars and staggered sowing dates.

- Avoid frost-prone paddocks, especially low-lying areas.

- Tactically cut hay when crops are frosted.

These strategies reduce losses in bad frost years — but they also come with trade-offs. For example, delaying wheat sowing lowers frost risk but shortens the growing season, often exposing crops to more heat stress at the finish and reducing yield in mild years.

🌱 This analysis was undertaken as part of the GRDC RiskWi$e project, in collaboration with Facey Group.